May 2025

How IIDA NC’s Climate Action Committee is Leading Change

Mobilizing the design community for bold, collective climate action.

In 2021, a group of designers from our IIDA Northern California Chapter came together to form the IIDA NC Climate Action Committee, with a shared goal: to take real, actionable steps toward addressing climate change within the interior design industry.

Laying the Foundation

In its first year, the Climate Action Committee supported critical decarbonization legislation at the state level, laying the groundwork for a more sustainable built environment across California. One of the committee’s foundational achievements was the creation of the IIDA Northern California Position Statement on Climate—a bold and unapologetic call for the design profession to lead in creating positive change. It was the first statement of its kind from any IIDA chapter.

Introducing the Climate Crawl

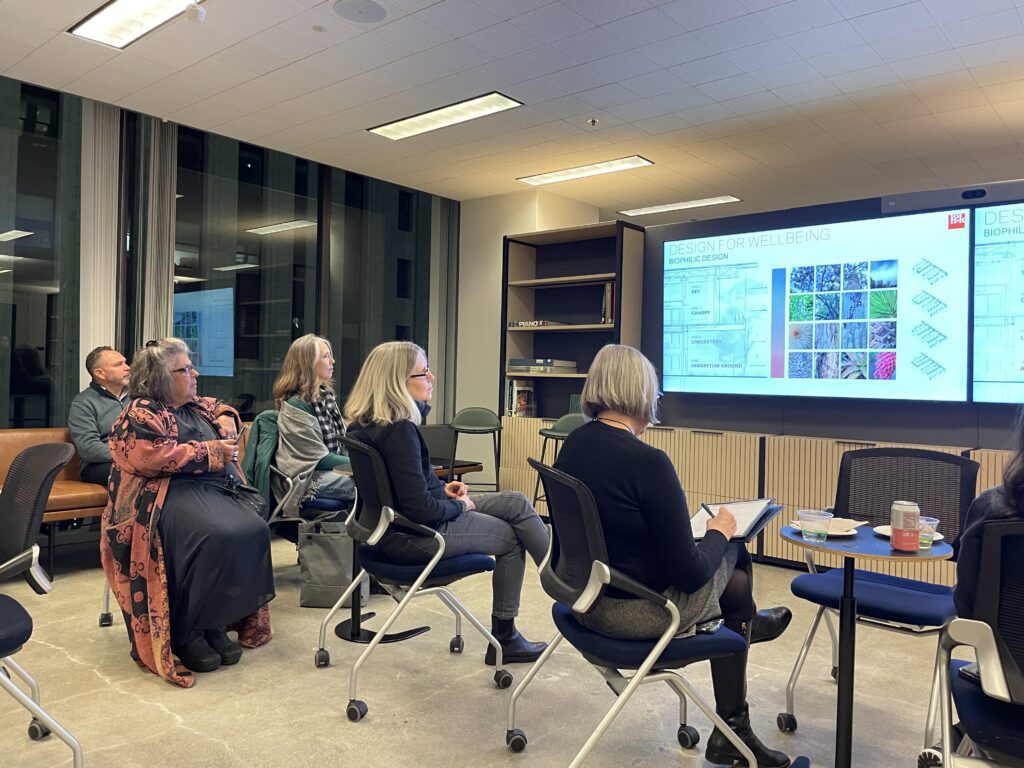

To engage the local Bay Area design community, the committee launched the Climate Crawl—a simple idea with powerful impact. The goal: gather design firms across San Francisco to share their climate journeys, successes, challenges, and resources. Every firm is at a different point in its journey, and there’s so much we can learn from one another.

Each month, a different firm hosts the group, sharing how they’re rethinking materials, processes, and priorities to combat climate change. Now in its fourth year, the Climate Crawl continues to grow. It’s become a model for how knowledge-sharing can drive real progress—especially in an industry where every project has the power to shape a more sustainable future.

Building a Climate-Conscious Design Community

The IIDA NC Climate Action Committee serves as the working arm for all things climate-related within our chapter. Our mission is to inspire, educate, lead, and foster a design community that is both socially and environmentally responsible. We believe interior design plays a critical role in the climate conversation. From the materials we specify to the carbon footprint of our spaces, we have the power—and responsibility—to make better choices. And we know we’re stronger together.

Join the Movement

We’re just getting started. The committee continues to host panels, collaborative events, and the Climate Crawl to keep climate action at the forefront of our profession. With every conversation, every crawl, and every commitment, we move closer to an industry dedicated to designing a regenerative and resilient future.

We’d love for you to join us! If you’re passionate about climate and ready to take action, we welcome you to get involved. For more information, reach out to: verda@o-plus-a.com